As the number of unprecedented cyberthreats continues to rise, correspondingly the demand for cybersecurity professionals continues to surge in both public and private sectors. Unfortunately, the supply of cybersecurity professionals is NOT in equilibrium with the demand of cybersecurity professionals. If you were to view any ‘top 10’ jobs, most likely ‘cybersecurity’ will rank high on the list of jobs. It may even rank in the top 5 on the list. But why is cybersecurity so hot? What makes any job hot? High salary? Great benefits? How about incredible opportunities for career growth and world-wide job stability requirement? In a growing industry with a rapidly increasing job market, the cybersecurity field offers a diverse range of job prospects with considerably above normal salaries. However, despite these intrinsic career benefits and ever-expanding scope of cybersecurity, headlines repeatedly report a shortage of qualified job candidates, which ultimately results in a lack of resources to face an evolving cyber threat landscape. In response, more and more universities and colleges are doing their part, providing a variety of new cybersecurity degrees from coast to coast – both traditional and online programs. But it’s not enough. The candidate shortage continues, leaving resourceful organizations to consider recruiting and training potential ‘untapped’ talent pools within their own organizations.

Cultivating Cybersecurity Talent Internally

The cybersecurity workforce is the focus of a recent Forbes study that reports 40,000 information security analyst positions and 200,000 other cybersecurity roles go unfilled every year in the US. With current talent deficits like these, the likelihood of employers adequately staffing a cybersecurity workforce into the near future appears bleak.1

In fact, data aggregator, Cybersecurity Ventures, which synthesizes dozens of employment and industry sources globally, predicts 3.5 million cybersecurity positions will go unfilled by 2021. This figure is even more riveting when compared to their accompanying estimate that cybercrime in 2021 will cost businesses globally more than $6 trillion annually (a 100% increase from $3 trillion in 2015).2

“New collar” internal candidates

Some forward-thinking organizations are answering this immense need for current and future qualified cybersecurity talent by cultivating cybersecurity talent internally. For instance, IBM focuses on capabilities not degrees, reports one IBM spokesperson. “If you’ve got the right skills, there’s a career for you at today’s IBM.” Indeed, candidates that fit this new perspective are termed, “new collar” candidates. The spokesperson explains, “New collar candidates who lack four-year degrees accounted for 15% of the company’s US hiring in 2017. That has allowed the company to pick from a diverse pool of candidates, many of whom would not be considered by other companies.” 3

Taking matters internally could be a strategic move for other companies as well. In fact, doing so could give employers who already boast diverse employee training resources – such as onsite classrooms, computer-based training, and job shadowing programs, a real advantage. According to a 2007 study published by Human Resources Development Quarterly which examined the relationship between job satisfaction and workplace training, training conducted using methods most preferred by employees led to greater overall job satisfaction. As a significant finding, employees in the study had a variety of training preferences, indicating diversity in training delivery methods is a desirable feature for workplace training.4

Cybersecurity training – no lack of offerings

Making the most of existing internal training resources is a great idea for many reasons. However, cybersecurity training content is highly specialized and the quickest route to such specialized content may be through third party training providers. Although the field of cybersecurity is relatively new and evolving, there is no lack of so-called “gurus,” and “qualified training providers,” hawking a multitude of certifications and other expensive training programs to an eager corporate community.

So how does an employer sift through a sea of such offerings to ensure their training dollars are wisely invested? How do they identify the best internal candidates to develop? And how do they develop training roadmaps to ensure the right skills are developed, and career development paths exist?

NICE answers for developing a cybersecurity workforce

The answers to identifying and developing a cybersecurity workforce can be found within the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE) Cybersecurity Workforce Framework (NICE Framework). This Framework emerged as a special initiative of the Comprehensive National Cybersecurity Initiative (CNCI), to develop a skilled cyber workforce of people with necessary knowledge and skills.

According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), “NICE,” can help “identify training and qualification requirements to develop critical Knowledge, Skills, and Abilities (KSAs) to perform cybersecurity Tasks” for over fifty common work roles. To accomplish this comprehensive goal, NICE contains seven cybersecurity categories comprised of a varying number of specialty areas.5

Additionally, as of July 6, 2018, NICE now offers Capability Indicators for entry level, intermediate, and advanced job levels – these are the combination of education, certification, training, experiential learning, and continuous learning attributes that could indicate a greater likelihood of a candidate’s ability to perform a given cybersecurity work role. In fact, Tasks, KSAs, and Capability Indicators for each job role are easily accessed online via an interactive framework tool provided by the organization best known for connecting government employees, military, students, educators, and industry with cybersecurity training providers across the country, the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Careers and Studies (NICCS).6

Impressively, Capability Indicators are the result of many years of extensive analyses validated by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), with focus group participation from across the US., including private industry, academia, and government.

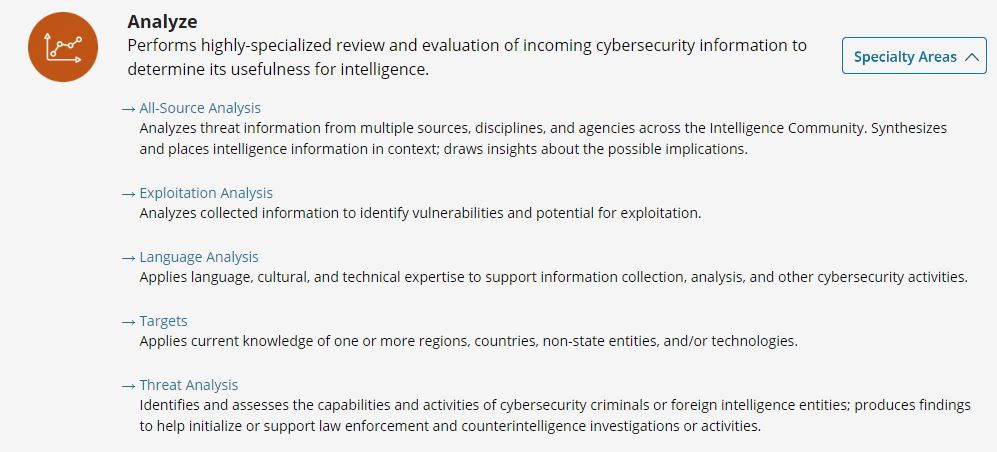

For first-hand experience with the interactive components of the online NICE tool provided by NICCS, go to https://niccs.us-cert.gov/workforce-development/cyber-security-workforce-framework, and select the first category, ‘Analyze’ from the colorful menu presented (see Figure 1).

When selected, the Analyze category displays six specialty areas as a drop-down menu. Select the last specialty area, ‘Threat Analysis,’ and cybersecurity workforce information for its one related work role, ‘Threat/ Warning Analyst (AN-TWA-001),’ is presented. The role’s full complement of Tasks, Capability Indicators, and KSAs are presented. A listing of ‘Related Courses,’ which provide recommended training options is also presented.

Note, Related Courses are aligned to the extensive NICCS Education and Training Catalog which features over 3,000 NICCS-vetted courses from industry-leading training providers. An extra feature is a US. map search tool which can quickly locate a variety of nearby training offerings (see Figure 2).

NICE implementation

In August of last year, Virginia became the first US state to formally adopt NICE for its cybersecurity training and hiring efforts. At that time, former Virginia Governor, Terry McAuliffe, explained, “Adding this framework to our current efforts led by the Secretaries of Technology, Education, Commerce and Trade, and Administration will strengthen the commonwealth’s ability to address the high demand for skilled cyber security professionals and enhance our position as a global leader in cyber security.” He added, “Virginia has one of the highest concentrations of cyber professionals in the country, but we need to continue to evolve our workforce education and training efforts to support Virginia’s businesses as they work to meet the challenges of data security and integrity and thwart compromising cyberattacks.” 7

Summary

So, while leading studies may show demand for cybersecurity job candidates is far out-pacing supply today and into the near future, as Einstein said, “in the middle of difficulty lies opportunity.” Several years in the making, the NICE Framework represents a valuable opportunity for savvy employers – whether in private, public, or academic organizations – to identify capabilities required for internal training candidates and understand qualifications for over fifty cybersecurity job roles at all levels of experience.

Indeed, pairing the NICE Framework with existing internal training resources could bridge the gap between great idea and more immediate, viable solution for employers seeking to cultivate internal cybersecurity talent while leveraging current training investments. (To learn more about the NICE Framework visit the NICCS web link included in the body of this article, or visit: https://www.nist.gov/itl/applied-cybersecurity/nice/resources/nice-cybersecurity-workforce-framework.)

References

- J. Kauflin. (2017) The Fast-Growing Job With A Huge Skills Gap: Cyber Security. Forbes Staff. Online. Available: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jeffkauflin/2017/03/16/the-fast-growing-job-with-a-huge-skills-gap-cyber-security/#5dcd91035163

- S. Morgan. (2017) Cybersecurity Jobs Report 2018-2021. Online. Available: https://cybersecurityventures.com/jobs/

- D. Kline. (2018) Tech Giant Follows a Different Path to Filling Open Jobs. Online. Available: https://www.fool.com/careers/2018/07/09/tech-giant-follows-a-different-path-to-filling-ope.aspx

- S. Schmidt. (2007) The Relationship Between Satisfaction with Workplace Training and Overall Job Satisfaction. Online. Available: https://scholarworks.iupui.edu/bitstream/handle/1805/276/Schmidt.pdf

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). (2017) National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE) Cybersecurity Workforce Framework, SP 800-181. Online. Available: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-181.pdf

- National Initiative for Cybersecurity Careers and Studies (NICCS). Online. Available: https://niccs.us-cert.gov/workforce-development/cyber-security-workforce-framework

- CISO Mag, (2017) Virginia adopts NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework. Online. Available: https://www.cisomag.com/virginia-adopts-nice-cybersecurity-workforce-framework/