Every activity a person carries out on the Internet leaves behind a trail of data commonly known as a digital footprint. The information left behind can have real-world consequences. As such it is essential that users understand how their digital footprint is created, the magnitude of that digital trail, and the steps they can take to reduce their digital footprint to manage and protect their privacy on the Internet.

What is a digital footprint?

A digital footprint is the trail of data left behind by a person when they carry out activities online. Whether posting to social media, shopping for gifts, commenting on videos, or sending an email, data is created that could be used to identify a person and their interests. Digital footprints can be separated into two different categories depending on how the information is shared with the entity collecting user data.

The first type of digital footprint is a person’s active digital footprint. A person’s active digital footprint is created when they voluntarily put information about themselves online. Contributions to a person’s active digital footprint require interaction. For example, when a person registers for an account on a website, they may be asked to provide information about themselves such as their first and last name, email address, and other personal information. In this registration scenario, the person is actively choosing to provide this information to the website. Old images, likes, and posts that users at one point wanted to be viewed contribute to their active digital footprint. By consciously making a decision to post this information online, data is left online that can be collected, searched, and possibly sold in the future.

On the other hand, a passive digital footprint is the data collected by companies and other organizations without the active participation of the person leaving the trail. The information that composes a user’s passive digital footprint is gathered in the background, and the person may not even realize it is being collected. For instance, when a person browses the Internet, the sites they visit may record the pages that were visited and the IP address that was involved in that web request. While site log information can be used by site administrators to troubleshoot problems, it is also of interest to advertisers. Passive digital footprints can be used to target advertisements to people in specific locations or to identify a person’s interests based on their browsing habits.

Why is it harmful?

It is critical that people understand that the actions they take online contribute to their digital footprint and may have real-world consequences. An individual’s digital footprint could damage his or her reputation, may be shared by organizations, and possibly could be obtained by hackers and identity thieves. With the widespread popularity of numerous social networking sites such as Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn, the availability of data regarding individuals has grown. People must keep in mind that tweets, replies, likes, and photos cannot only be seen by friends and family but also by recruiters and the companies that the person might apply to. The information that can easily be found online gives employers insight into a candidate before ever meeting face to face. According to CareerBuilder, “Seventy percent of employers use social networking sites to research job candidates” and “57 percent have found content that caused them not to hire candidates” (2018). The reasons why job candidates were not hired included the posting of inappropriate content, discussing personal drinking and drug use, posting discriminatory comments, and complaining about previous employers or coworkers (CareerBuilder, 2018). Think twice before posting, as it is the user’s responsibility to create an accurate reflection of themselves online.

In addition to potentially costing someone a job and damaging their reputation, a person’s digital footprint can be used by malicious actors to steal the person’s identity. By analyzing the data that is available online, malicious actors can learn where a person lives, the email addresses that they use, what they like, and more. If an attacker knows a person’s email address, it is possible that they could gain access to email accounts by either brute forcing or guessing the password. Once they have access to the email account, they could reset the password for other accounts, as the account reset notification/request is typically sent to a person’s email address. Account access additionally allows malicious actors to view profile fields that may be hidden to the other users. Collecting the information available online about a target user allows these malicious actors to craft a more convincing false identity that can then be traded online, used to open bank accounts, apply for loans, or even receive medical care.

Unfortunately, cybercriminals are not the only ones collecting individuals’ personal information. Entities known as data brokers often collect information that comprises an individual’s digital footprint. Data brokers are companies that gather publicly available user data to exchange or sell to other companies or individuals (Grauer, 2018). They collect information from sources like court and property records, warranty registrations, social media sites, and census data. Once gathered, data brokers make money by selling user data to other individuals online, or again, to advertisers for marketing purposes (Grauer, 2018). For instance, if users have ever searched for someone online and ended up at a people search site, chances are they are interacting with a data broker. Not only do data brokers allow anyone to purchase information, but they also store data from an abundance of individuals in one location, data that can be exposed if these companies are breached.

Perhaps the best illustration of how a person’s digital footprint can get out of hand and be used without their permission is the current scandal occurring with Facebook user data. In March of 2018, it was discovered that a political consulting firm named Cambridge Analytica gathered data from up to 87 million Facebook users. The information was collected through a Facebook app called “thisisyourdigitallife” which allowed users to take a personality quiz. However, the application also granted the developer the ability to collect profile information from not only the user who took the quiz, but also from the user’s friends (Sanders & Patterson, 2018). Once users provide data to companies, it is out of their control. Users are trusting that the companies will act responsibly in handling their personal information.

How can people protect themselves?

Regulations

With data breaches becoming commonplace, governments have begun to put laws in place to help improve users’ control over the information that exists about them online. The primary and most well-known regulation protecting user privacy is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) passed by the European Union (EU). GDPR is a set of standards that govern how personal data can be stored and shared among companies. While GDPR was implemented with European citizens in mind, it has broader reaching effects. Any business operating in countries outside of the EU that provide services to European citizens are also affected by GDPR. More specifically, those organizations that either control the data of citizens in the EU or process this personal data will be responsible for meeting GDPR compliance specifications (Palmer, 2018). With an understanding of what GDPR is, users need to understand the actions that they can take to utilize these protections to their advantage.

While GDPR provides various rights to users, two primary rights that change user interaction with their personal data. Arguably the most significant rights granted to users under GDPR are the right of access and the right to erasure. The right of access, like the name suggests, allows users to obtain information from website/organizations that are in control of their data. Users can submit a request to an organization to determine if that organization is processing their personal information. The receiving organization then has thirty days from the date the request was made to respond to that request. If the controller is processing a user’s data, individuals can then obtain information about what data is being processed, why it is being processed, how long that data will be stored, who it will be shared with, and whom the data came from (if the individual did not provide the data to the controller themselves). When responding to a request, organizations are required to provide users with an initial copy of the information they are storing (for free) and to inform them of other rights granted to them under GDPR (Official Journal of the European Union, 2016).

While the right of access provides people with a better understanding of the data that companies are collecting, the right to erasure allows them to take action. The right to erasure, often referred to as the “right to be forgotten,” enables users to request that organizations controlling their information remove the personal data that they have obtained. Users can have their personal information removed if their data is not applicable to why it was initially collected, if they no longer consent or object to their data being processed, or if they feel that their data is not being processed lawfully. For example, if a person opens a credit card with a credit card company and provides their address, that person should be able to close their account and remove their personal information to stop receiving mail from that company after they have no remaining balance. However, the right to erasure does not apply in all situations. If there are other legal or legitimate grounds for processing a user’s information, such as an organization is legally obligated to collect it, or it is used for the public interest, organizations can deny these requests (Official Journal of the European Union, 2016). Together, the right to access provides users with more control over their data by allowing them to learn the type and extent of personal information stored and delete that data to reduce their digital footprint.

The second and perhaps lesser known law concerning user privacy and control of data is the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). The CCPA requirements go into effect on January 1st, 2020, changing the way businesses collect and process data of Californians. Unfortunately, it appears that only larger companies will have to comply with CCPA, as they have to be for profit, make over $25 million in revenue a year, and either primarily make that money by selling Californians’ personal information or receive and share the information of over 50,000 Californians a year. Like GDPR, CCPA requires that businesses respond to requests from users regarding the data they have collected, who provided the data, why it was collected or sold, and who it is shared with. Under CCPA, personal information is widely defined. For example, not only does “personal information” include standard data like a person’s name, address, phone number, SSN, but it also covers information such as geolocation data, biometric data, and profiles of the person’s preferences/tendencies. Knowing what personal information companies have collected from them, Californians can then opt out of the sale of this data without fear of differential treatment for doing so. Additionally, if they prefer, users can also have their personal information be deleted upon request (Chau, Hertzberg, & Dodd, 2018).

Direct Action

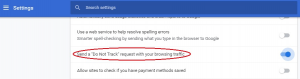

One step that people can take to protect their privacy online is to enable “Do Not Track” in their web browsers. Do Not Track is a web browser setting that sends extra data in the form of a header letting sites know that a user does not want to be tracked (Future of Privacy Forum, n.d.). Popular web browsers such as Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, and Mozilla Firefox allow users to turn on Do Not Track easily. For Instance, in Chrome, users can click on “Customize and control Google Chrome” (the three dots in the upper right-hand corner of the browser and go to settings). Under settings, advanced, there is a section labeled “Privacy and Security” containing various options that users can enable or disable to control how their data is handled when browsing the web. Do Not Track can be enabled by clicking the slider for “Send a “Do Not Track” request with your browsing traffic.” A popup will then ask the user to confirm that they would like to enable Do Not Track and provides a short description of what the request does. Figure 2 below displays the Do Not Track setting enabled in Google Chrome.

While Do Not Track is easy for users to enable, it is critical to recognize the setting has its own set of limitations. Do Not Track does not limit a user’s digital footprint when they are browsing most sites on the Internet. The largest sites that honor do not track requests are Pinterest and Medium, while the vast majority of other sites on the Internet ignore these requests. The same sites that ignore these requests have nothing to fear from ignoring the requests because there is no penalty in place to enforce and therefore legitimize Do Not Track. Additionally, the specific actions that are taken by websites when users ask not to be tracked vary since there is no accepted industry standard. While sites like Medium prevent tracking by not sending user data to third parties when users are not logged in (blocking targeted ads), there is no consensus that this is what Do Not Track should be used for (Hill, 2018a). Users should keep these limitations in mind when utilizing Do Not Track, recognizing that it is not a silver bullet when it comes to protecting their privacy and reducing their digital footprint.

A second method users can exercise when attempting to limit their digital footprint is to provide fake information to sites. Any time users register for an account on websites it is common that they will be asked to provide personal information. The information requested when registering for sites typically includes full first and last name, address, email address, and phone number. However, this process can be especially tedious if users are forced to sign up when they are just trying to access the site once to view its content and do not plan on coming back. If they would like, users could enter incomplete or inaccurate data into sites to not only limit the amount of data organizations can collect and sell about them, but also prevent themselves from being found when others are searching for them on search engines. As always, it is recommended that users first check websites terms of service to see if false information is prohibited in some profile fields.

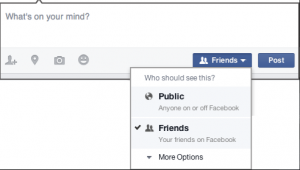

Thirdly, social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram offer privacy settings that users can change to reduce the amount of information available about them online. Privacy settings provide users with the ability to choose who can access their images and other information posted online. Everyone should take time to look into these privacy settings to lock down their accounts, while still being able to use them to share information with friends and family. While an exhaustive list would be extensive, take the privacy settings available to users on Facebook for example. As shown in Figure 3 below, Facebook allows users to change the visibility of their posts to either anyone or just their friends on Facebook when they make a new post. Users also have the option to prevent people from being able to find their Facebook profile if they know the person’s email address or phone number. Additionally, they can prohibit apps, websites, and games from accessing their user data. By adjusting the privacy settings that exist on social networking websites, users can reduce their digital footprint by limiting the ability of others to find their account and minimize the information that is shared with sites.

Speaking of Facebook and privacy settings that users can take advantage of, users should avoid checking in at locations and turn off location services when browsing the Internet. Voluntarily providing location information and utilizing location services allows malicious actors to know where users are. Location data is especially concerning if the person has a stalker or is headed out of town and is afraid of someone breaking into their house while they are away. Furthermore, it gives websites data they can use to target ads to users. Remember that all of this information can be used to put together a profile of who the person is, what they like, and what they might buy. Unfortunately, a person’s location can still be determined through other means, such as their IP address and profile information. As such, in addition to stopping checking in and turning off location services, users may want to utilize a Virtual Private Network (VPN) or remove apps that appear to be targeting ads (Hill, 2018b).

A fourth technique users can take advantage of to reduce their digital footprint is to use a VPN when browsing the Internet. A VPN is a secure tunnel that encrypts a user’s communications from their network to an exit node located elsewhere (Symanovich, 2019). Imagine a user is browsing the web at a local coffee shop or is connected to hotel Wi-Fi. They are trusting that the other users on that network are not eavesdropping on their internet traffic. A VPN encrypts this traffic preventing outsiders from spying on users who may be checking their bank account, shopping online, or conducting other activity that may expose their personal information. The user’s location and IP address are also hidden when connected to a VPN. Web requests appear to be coming from the chosen endpoint with its own IP address and location. Users are then protected from the tracking mentioned previously because their browsing/search history cannot be traced back to their IP address (Symanovich, 2019). By encrypting communication and masking the user’s IP address and location, a VPN can limit a person’s digital footprint.

Even with the benefits that VPN services can provide, it is essential that people do their research before choosing a VPN service to use. People who wish to take advantage of the privacy and security advantages of VPN services must make sure the service that they go with can be trusted. Users are relying on the VPN provider to respect their privacy and not collect or sell their data. When trying to decide on whether or not to go with a particular provider, make sure to read through their logging policies thoroughly. Some providers will log the user’s browsing activity, while others say they do not collect any logs. Logging is a point of contention for privacy-focused users because VPN services are subject to the data collection laws of the country they are based in (Hunt, 2017). As such, many users take this into account when shopping for a VPN service along with other factors such as price, internet speed, features, and the number of supported devices. Users need to do their research to ensure that the VPN provider they choose will provide the services that they advertise. If they feel that they cannot trust VPN service providers, there are other actions people can take to reduce their digital footprint.

Removing old accounts that users do not log into anymore is a fifth way people can reduce their digital footprint. How many people still have old accounts for sites that they have completely forgotten about? The problem with these forgotten accounts is that they still contain personal information about users such as their full name, names of relatives, birthdays, the things that they like, and potentially even where they used to or still live. As mentioned previously, all this personal information can be used by malicious actors to steal a person’s identity or gain access to their accounts. When people leave information in accounts that they have abandoned, that information is at risk of being exposed in the event of a data breach (Osborne, 2018). If users do not have the option to delete their accounts, they can alternatively remove the data from fields that allow it or provide fake information.

A sixth option that users can make use of to reduce their digital footprint is to use the private browsing options that are in their browsers or use privacy-focused browsers. Popular web browsers such as Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, and Mozilla Firefox all have “private” browsing modes. Chrome allows users to go incognito, while Firefox and Edge give the user the option to open private windows. The private browsing modes offered in popular browsers enhance user privacy (and reduce their digital footprint) by having different default settings than if users were browsing normally. Generally, by default, when surfing the Internet, cookies, browsing history, and form data will be saved. However, when utilizing the private browsing modes in the previously mentioned browsers, this convenience-oriented information is not retained but is deleted when the user closes the browsing window. As typically specified in the disclaimers when the user opens new private windows, internet service providers and employers (if browsing at work) can still see the user’s internet traffic.

Last but not least, people should search for their name. By searching for their name in search engines like Google and DuckDuckGo, a person can identify what other individuals can find out about them and how large their digital footprint currently is. It is recommended that people not only look up their full name in text and image searches but other variations of their name as well (Howell, 2015). If a person knows what is already out there on the Internet about them, it makes cleaning up and reducing their digital footprint that much easier. They can then log into sites that still contain their information to remove it. Though, if they have forgotten passwords to the site in question or feel that the information provided about them should not exist, they can contact the site administrator to have that information removed. Search results will not be removed immediately, as Google and other sites index them, but slowly less and less information will be available on the person as they remove information that exists about them from the Internet.

Summary

When people watch videos, make posts, and shop online, they leave behind a trail of data known as their digital footprint. While this data can help them get noticed on the internet when looking for jobs or trying to grow an audience, their digital footprint can be harmful as well. Companies can sell or trade user information, and malicious actors can use it to steal an individual’s identity. Governments have begun passing legislation to provide users in specific locales with rights that are affecting the options available to users everywhere. Nonetheless, it is ultimately up to the user to regulate the information that exists about them online and find a balance between privacy and discoverability.

References

- CareerBuilder. (2018, August 9). More Than Half of Employers Have Found Content on Social Media That Caused Them NOT to Hire a Candidate, According to Recent CareerBuilder Survey. Retrieved from http://press.careerbuilder.com/2018-08-09-More-Than-Half-of-Employers-Have-Found-Content-on-Social-Media-That-Caused-Them-NOT-to-Hire-a-Candidate-According-to-Recent-CareerBuilder-Survey

- Chau, A., Hertzberg, S., & Dodd, S. (2018, June 28). AB-375 Privacy: Personal information: Businesses. Retrieved from https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billStatusClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180AB375

- Future of Privacy Forum. (n.d.). All About DNT. Retrieved from https://allaboutdnt.com/

- Grauer, Y. (2018, March 27). What Are ‘Data Brokers,’ and Why Are They Scooping Up Information About You? Retrieved from https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/bjpx3w/what-are-data-brokers-and-how-to-stop-my-private-data-collection

- Hill, K. (2018, October 15). ‘Do Not Track,’ the Privacy Tool Used by Millions of People, Doesn’t Do Anything. Retrieved from https://gizmodo.com/do-not-track-the-privacy-tool-used-by-millions-of-peop-1828868324

- Hill, K. (2018, December 18). Turning Off Facebook Location Tracking Doesn’t Stop It From Tracking Your Location. Retrieved from https://gizmodo.com/turning-off-facebook-location-tracking-doesnt-stop-it-f-1831149148

- Hunt, T. (2017, April 6). The importance of trust and integrity in a VPN provider (and how MySafeVPN blew it). Retrieved from https://www.troyhunt.com/the-importance-of-trust-and-integrity-in-a-vpn-provider-and-how-mysafevpn-blew-it/

- Howell, D. (2015, April 22). How to protect your privacy and remove data from online services. Retrieved from https://www.techradar.com/news/internet/how-to-protect-your-privacy-and-remove-data-from-online-services-1291515

- Official Journal of the European Union. (2016, April 27). Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council. Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=OJ:L:2016:119:FULL

- Osborne, C. (2018, December 18). Remove yourself from the Internet and erase your online presence. Retrieved from https://www.zdnet.com/article/how-to-erase-your-digital-footprint-and-make-google-forget-you/

- Palmer, D. (2018, May 23). What is GDPR? Everything you need to know about the new general data protection regulations. Retrieved from https://www.zdnet.com/article/gdpr-an-executive-guide-to-what-you-need-to-know/

- Sanders, J., & Patterson, D. (2018, December 11). Facebook data privacy scandal: A cheat sheet. Retrieved from https://www.techrepublic.com/article/facebook-data-privacy-scandal-a-cheat-sheet/

- Symanovich, S. (2019). What is a VPN? Retrieved from https://us.norton.com/internetsecurity-privacy-what-is-a-vpn.html